How Microphones Work

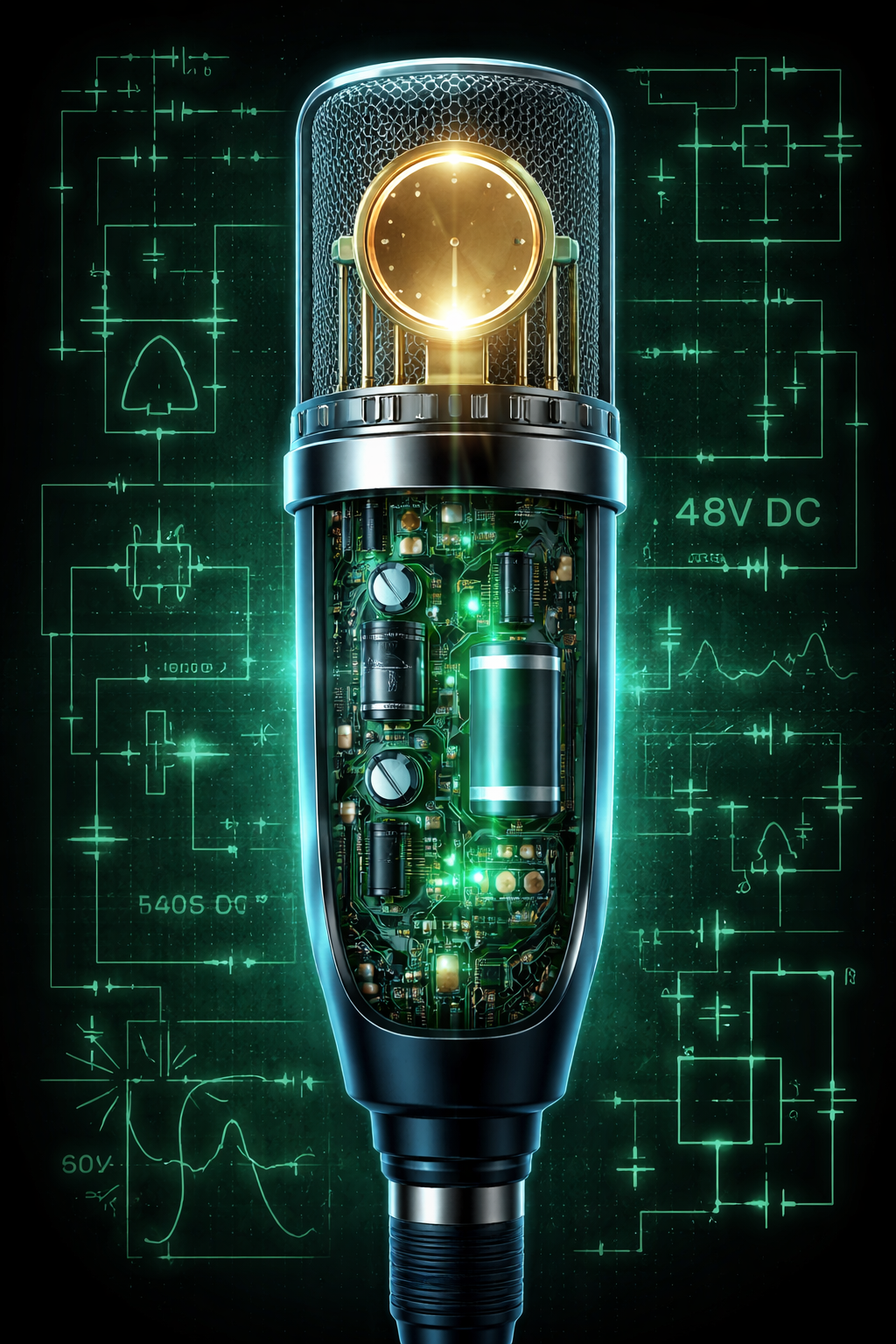

A detailed look inside the mic, breaking down capsules, active electronics and phantom power.

Ian Gardner is a British-American broadcaster, voice artist and audio enthusiast, sharing years of experience building creative workflows from a modern home studio. He helps readers make smarter buying decisions across studio gear, production tools and home comforts for both inside and outside the workspace. Broadcasters, podcasters, voice artists, producers and digital creators will find guidance that supports high production values and efficient workflows for building a successful home studio business.

Microphones feel like magic. You speak, sing, clap, or drop a spoon, and somehow that physical chaos turns into a clean electrical signal that can be recorded, amplified, streamed, or mangled into autotuned glory. Under the hood, though, microphones are not magic at all. They are beautifully fussy pieces of electronics that sit at the intersection of physics, materials science, and signal theory. Once you understand what is actually happening inside the grille, microphones become even more impressive.

At the most basic level, every microphone does the same job. It converts changes in air pressure into changes in voltage. Sound waves push and pull on something that can move. That movement is translated into an electrical signal that mirrors the original sound waveform. How that translation happens depends almost entirely on the capsule, which is the heart of the microphone.

The capsule is the transducer. In a dynamic microphone, the capsule consists of a diaphragm attached to a coil of wire suspended in a magnetic field. When sound waves hit the diaphragm, it moves the coil back and forth through the magnetic field. Thanks to electromagnetic induction, that motion generates a tiny electrical current. Louder sounds move the coil more, producing higher voltage. Quieter sounds barely tickle it. This design is mechanically simple, electrically passive, and famously tough. That is why dynamic microphones can survive drops, moisture, and the occasional attempt to eat one on stage.

Condenser microphones use a very different approach. Their capsules are based on capacitance. A condenser capsule has two conductive plates - one fixed backplate and one ultra-thin diaphragm that can move. Together, they form a capacitor. When sound waves hit the diaphragm, the distance between the plates changes. That change alters the capacitance, which in turn changes the voltage across the plates. This design is extremely sensitive because the diaphragm is incredibly light. It can respond to tiny pressure changes that a dynamic diaphragm would ignore entirely.

Sensitivity, however, comes with a cost. A condenser capsule needs power to work. This is where phantom power enters the story. Standard studio condensers rely on 48 volts DC supplied through the microphone cable. Phantom power polarizes the capsule and powers the internal impedance conversion circuitry. It is called phantom power because it travels invisibly over the same balanced audio lines that carry the signal, without interfering with devices that do not need it.

Impedance is one of the least glamorous but most important concepts in microphone design. The raw signal coming from a capsule is extremely high impedance and very low current. If you tried to run that signal directly down a cable, it would be noisy, weak, and prone to high-frequency loss. To fix this, condenser microphones include an internal impedance converter, often based on a field-effect transistor. This stage lowers the output impedance so the signal can travel down long cables without falling apart. Dynamic microphones, by contrast, naturally produce a lower impedance signal and usually do not require active electronics.

Noise is the great enemy of microphones, especially high-sensitivity designs. Every electronic component produces noise due to thermal agitation of electrons. This is called Johnson noise, and it sets a hard physical limit on how quiet a microphone can be. Designers fight noise by using high-quality resistors, minimizing circuit complexity, and carefully biasing active components. Capsule noise also matters. Air molecules colliding with the diaphragm create random motion, which becomes self-noise. This is why extremely sensitive microphones often list an equivalent noise level in decibels. Lower numbers mean quieter electronics.

High sensitivity microphones amplify everything, including room tone, HVAC rumble, and the existential dread of your untreated home studio. Sensitivity is not about being better. It is about being appropriate. A high-sensitivity condenser excels at capturing subtle detail, transients, and nuance. A lower-sensitivity dynamic microphone can reject background noise and handle absurd sound pressure levels without distortion. Neither is inherently superior. They are tools optimized for different problems.

Another key factor is frequency response, which is shaped both by physics and electronics. The size and tension of the diaphragm affect how it responds to different frequencies. Larger diaphragms tend to have better low-frequency response but slower transient behavior. Smaller diaphragms react faster and often produce more accurate high-frequency detail. Internal acoustic chambers, ports, and resonators further shape the sound before it ever becomes an electrical signal. By the time the signal hits the output connector, it has already been sculpted.

Balanced outputs are the final piece of the puzzle. Most professional microphones use balanced connections with three pins. Two pins carry the audio signal in opposite polarities, and the third is ground. Any noise picked up along the cable is induced equally on both signal lines. At the preamp, the two signals are recombined, and the noise cancels itself out. This common-mode rejection is why microphones can run hundreds of feet of cable without turning into radio antennas.

When you put it all together, microphones are not just sound pickers. They are precision instruments that manage energy conversion, impedance matching, noise suppression, and signal integrity in real time. The next time you speak into one, remember that your voice is physically moving atoms, flexing membranes thinner than a human hair, and nudging electrons into orderly motion. That tiny electrical dance is the foundation of every recording, broadcast, and performance you have ever heard.

At the most basic level, every microphone does the same job. It converts changes in air pressure into changes in voltage. Sound waves push and pull on something that can move. That movement is translated into an electrical signal that mirrors the original sound waveform. How that translation happens depends almost entirely on the capsule, which is the heart of the microphone.

The capsule is the transducer. In a dynamic microphone, the capsule consists of a diaphragm attached to a coil of wire suspended in a magnetic field. When sound waves hit the diaphragm, it moves the coil back and forth through the magnetic field. Thanks to electromagnetic induction, that motion generates a tiny electrical current. Louder sounds move the coil more, producing higher voltage. Quieter sounds barely tickle it. This design is mechanically simple, electrically passive, and famously tough. That is why dynamic microphones can survive drops, moisture, and the occasional attempt to eat one on stage.

Condenser microphones use a very different approach. Their capsules are based on capacitance. A condenser capsule has two conductive plates - one fixed backplate and one ultra-thin diaphragm that can move. Together, they form a capacitor. When sound waves hit the diaphragm, the distance between the plates changes. That change alters the capacitance, which in turn changes the voltage across the plates. This design is extremely sensitive because the diaphragm is incredibly light. It can respond to tiny pressure changes that a dynamic diaphragm would ignore entirely.

Sensitivity, however, comes with a cost. A condenser capsule needs power to work. This is where phantom power enters the story. Standard studio condensers rely on 48 volts DC supplied through the microphone cable. Phantom power polarizes the capsule and powers the internal impedance conversion circuitry. It is called phantom power because it travels invisibly over the same balanced audio lines that carry the signal, without interfering with devices that do not need it.

Impedance is one of the least glamorous but most important concepts in microphone design. The raw signal coming from a capsule is extremely high impedance and very low current. If you tried to run that signal directly down a cable, it would be noisy, weak, and prone to high-frequency loss. To fix this, condenser microphones include an internal impedance converter, often based on a field-effect transistor. This stage lowers the output impedance so the signal can travel down long cables without falling apart. Dynamic microphones, by contrast, naturally produce a lower impedance signal and usually do not require active electronics.

Noise is the great enemy of microphones, especially high-sensitivity designs. Every electronic component produces noise due to thermal agitation of electrons. This is called Johnson noise, and it sets a hard physical limit on how quiet a microphone can be. Designers fight noise by using high-quality resistors, minimizing circuit complexity, and carefully biasing active components. Capsule noise also matters. Air molecules colliding with the diaphragm create random motion, which becomes self-noise. This is why extremely sensitive microphones often list an equivalent noise level in decibels. Lower numbers mean quieter electronics.

High sensitivity microphones amplify everything, including room tone, HVAC rumble, and the existential dread of your untreated home studio. Sensitivity is not about being better. It is about being appropriate. A high-sensitivity condenser excels at capturing subtle detail, transients, and nuance. A lower-sensitivity dynamic microphone can reject background noise and handle absurd sound pressure levels without distortion. Neither is inherently superior. They are tools optimized for different problems.

Another key factor is frequency response, which is shaped both by physics and electronics. The size and tension of the diaphragm affect how it responds to different frequencies. Larger diaphragms tend to have better low-frequency response but slower transient behavior. Smaller diaphragms react faster and often produce more accurate high-frequency detail. Internal acoustic chambers, ports, and resonators further shape the sound before it ever becomes an electrical signal. By the time the signal hits the output connector, it has already been sculpted.

Balanced outputs are the final piece of the puzzle. Most professional microphones use balanced connections with three pins. Two pins carry the audio signal in opposite polarities, and the third is ground. Any noise picked up along the cable is induced equally on both signal lines. At the preamp, the two signals are recombined, and the noise cancels itself out. This common-mode rejection is why microphones can run hundreds of feet of cable without turning into radio antennas.

When you put it all together, microphones are not just sound pickers. They are precision instruments that manage energy conversion, impedance matching, noise suppression, and signal integrity in real time. The next time you speak into one, remember that your voice is physically moving atoms, flexing membranes thinner than a human hair, and nudging electrons into orderly motion. That tiny electrical dance is the foundation of every recording, broadcast, and performance you have ever heard.

You may purchase items mentioned in this article here. Affiliate links earn me a commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for supporting IanGardner.com